my notes snipped while reading this book:

mpossible. Obviously, I am being slightly facetious here: this is not the only thing a PR department does. I’m sure in the case of Oxford much of its day-to-day concerns involve more practical matters such as attracting to the university the children of oil magnates or corrupt politicians from foreign lands who might otherwise have gone to Cambridge. But still,

“Most of the support covered basic computer operations the customer could easily google. They were geared toward old people or those that didn’t know better, I think.”

“Most of the support covered basic computer operations the customer could easily google. They were geared toward old people or those that didn’t know better, I think.”

“Our call center’s resources are almost wholly devoted to coaching agents on how to talk people into things they don’t need as opposed to solving the real problems they are calling about.”

12. There is certainly work on moralists in China, India, the classical world, and their concepts of work and idleness—for instance, the Roman distinction of otium and negotium—but I am speaking here more of the practical questions, such as when and where even useless work came to be seen as preferable to no work at all.

As the great classicist Moses Finley pointed out: if an ancient Greek or Roman saw a potter, he could imagine buying his pots. He could also imagine buying the potter—slavery was a familiar institution in the ancient world. But he would have simply been baffled by the notion that he might buy the potter’s time. As Finley observes, any such notion would have to involve two conceptual leaps which even the most sophisticated Roman legal theorists found difficult: first, to think of the potter’s capacity to work, his “labor-power,” as a thing that was distinct from the potter himself, and second, to devise some way to pour that capacity out, as it were, into uniform temporal containers—hours, days, work shifts—that could then be purchased, using cash.17

The English historian E. P. Thompson, who wrote a magnificent 1967 essay on the origins of the modern time sense called “Time, Work Discipline, and Industrial Capitalism,”23 pointed out that what happened were simultaneous moral and technological changes, each propelling the other.

Again, just sitting around, doing emails. Most days, I would go home early, because, why the fuck not?

well-educated young men and women without any real work responsibilities but with access to the internet—which is, potentially, at least, a repository of almost all human knowledge and cultural achievement—might spark some sort of Renaissance. Nothing remotely along these lines has taken place. Instead, the situation has sparked an efflorescence of social media (Facebook, YouTube, Instagram, Twitter): basically, of forms of electronic media that lend themselves to being produced and consumed while pretending to do something else. I am convinced this is the primary reason for the rise of social media, especially when one considers it in the light not just of the rise of bullshit jobs but also of the increasing bullshitization of real jobs.

or almost all, of their profits from their own financial divisions. GM, for example, makes its money not from selling cars but rather from interest collected on auto loans.

Now, in the fifties, sixties, and seventies, there was a tacit understanding in much of the industrialized world that if productivity in a certain enterprise improved, a certain share of the increased profits would be redistributed to the workers in the form of improved wages and benefits. Since the eighties, this is no longer the case. So here.

“Did they give any of that money to us?” our guide asked. “No. Did they use it to hire more workers, or new machinery, to expand operations? No. They didn’t do that, either. So what did they do? They started hiring more and more white-collar workers. Originally, when I started working here, there were just two of them: the boss and the HR guy. It had been like that for years. Now suddenly there were three, four, five, seven guys in suits wandering around. The company made up different fancy titles for them, but basically all of them spent their time trying to think of something to do. They’d be walking up and down the catwalks every day, staring at us, scribbling notes while we worked. Then they’d have meetings and discuss it and write reports. But they still couldn’t figure out any real excuse for their existence. Then finally, one of them hit on a solution: ‘Why don’t we just shut down the whole plant, fire the workers, and move operations to Poland?’ ”

Generally speaking, extra managers are hired with the ostensible purpose of improving efficiency. But in this case, there was little to be improved; the workers themselves had boosted efficiency about as much as it was possible to do

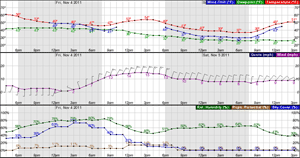

From roughly 1945 to 1975, there was what is sometimes referred to as a “Keynesian bargain” between workers, employers, and government—and part of the tacit understanding was that increases in worker productivity would indeed be matched by increases in worker compensation. A glance at the diagram on the next page confirms that this was exactly what happened. In the 1970s, the two began to part ways, with compensation remaining largely flat, and productivity taking off like a rocket (see figure 7).

These figures are for the United States, but similar trends can be observed in virtually all industrialized countries.

2. Technically the measure is “marginal utility,” the degree to which the consumer finds an additional unit of the good useful in this way; hence, if one already has three bars of soap stockpiled in one’s house, or for that matter three houses, how much additional utility is added by a fourth. For the best critique of marginal utility as a theory of consumer preference, see Steve Keen, Debunking Economics, 44–47.

12. Rutger Bregman, Utopia for Realists: The Case for Universal Basic Income, Open Borders, and a 15-Hour Workweek (New York: Little, Brown, 2017).

15. See, for instance, Gordon B. Lindsay, Ray M. Merrill, and Riley J. Hedin, “The Contribution of Public Health and Improved Social Conditions to Increased Life Expectancy: An Analysis of Public Awareness,” Journal of Community Medicine & Health Education 4 (2014): 311–17, which contrasts the received scientific understanding of such matters with popular perception, which assumes improvements are almost entirely due to doctors. https://www.omicsonline.org/open-access/the-contribution-of-public-health-and-improved-social-conditions-to-increased-life-expectancy-an-analysis-of-public-awareness-2161-0711-4-311.php?aid=35861.

Work, Aristotle insisted, in no sense makes you a better person; in fact, it makes you a worse one, since it takes up so much time, thus making it difficult to fulfill one’s social and political obligations.